Braun’s tubes became the Kleenex of the CRT age, still known as Braunsche Röhre in German and Buraun-kan in Japanese. Braun built cathode ray tubes-vacuum tubes with an electron emitter and a fluorescent screen-to help him see electrical waveforms on the first oscilloscopes, something previously done by hand and on paper. Thompson showed that cathode rays were electrons passing through a vacuum. As always, there’s a dispute over who was actually first. Both men did fundamental work in the physics of electromagnetism. Thompson and Karl Ferdinand Braun, who lived in England and Germany, respectively. Hobbes argued the contraption wasn’t any more significant than a “ pop gun.” Even if the pump worked, he asked, who could come to this exclusive club called the Royal Society to see it? The contraption had to be shown to work always and everywhere-and, if it didn’t, what is certainty, then?Īs Boyle tried to respond to Hobbes with ever-increasing specificity, he helped create the literary genre of peer-reviewed scientific papers.įast forward to the 19th century, when working CRTs depended on experimenters J.

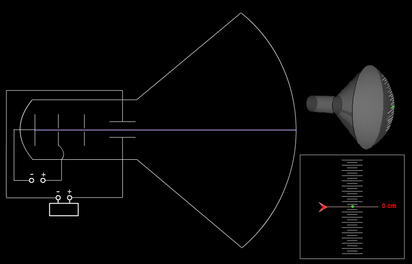

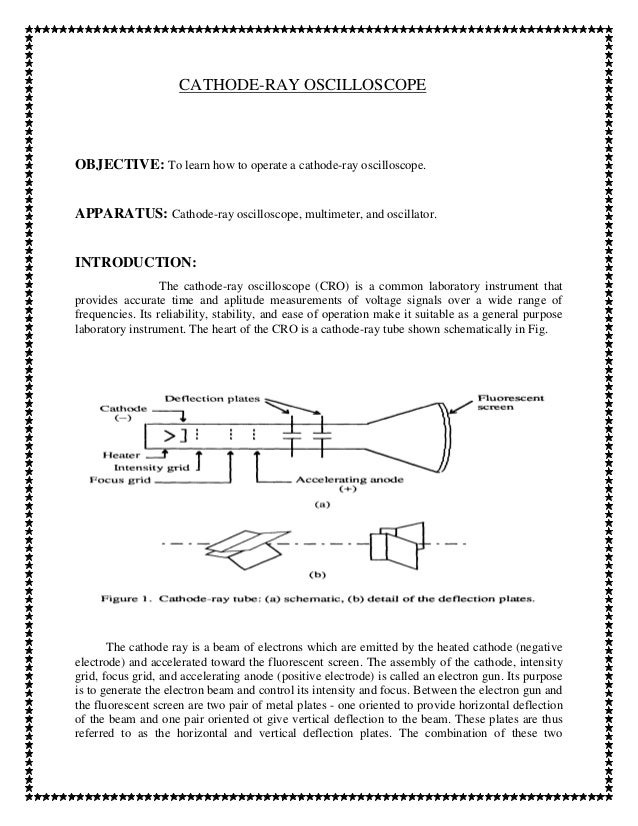

Hobbes ridiculed the air-pump demonstrations, which Boyle had completed in front of the brand new Royal Society of London for Improving Natural Knowledge. Through what we now call experimentation, competing claims to knowledge and authority could be judged without recourse to violence. The stakes were unimaginably high in the midst of violent crises over authority and control in England and on the Continent (both the English Civil War and the Thirty Years War raged during the Hobbes-Boyle debate).īoyle, using a vacuum pump-a seriously cutting-edge technology in those days-was trying to make the case that a radically new form of demonstration promised secure, indisputable knowledge. It pitted Thomas Hobbes, the arch political theorist, against Robert Boyle, a fashionable aristocrat, in a fight about the very meaning and demonstration of certainty. In 17th-century England the existence or non-existence of the vacuum was at the center of one of the greatest controversies of the modern era. The CRT is technologically fundamental to modern seeing, yet its inner workings depend on something completely invisible: a vacuum. What kind of life did the CRT lead? An extraordinary one, and an extraordinarily long one for a technology integral to an age of obsolescence. What does it mean that we think of the CRT as something with a life-something that was born, lived, died?

The obvious play on words conjoins an industrial mythos with a Christian burial rite in a requiem for an object that had, not long before, been the primary screen on which many of us experienced television, video, and computing.

“Rust in peace,” ministered the New York Times in its 2009 catalogue of obsolescence for the aughts.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)